Indian scientists are ushering in a new era of crop improvement with the development of TnpB, a compact and efficient genome-editing tool. Developed at ICAR-CRRI and now patented in India, TNPB provides a domestic alternative to CRISPR systems, enabling fast, accurate and economical development of stress-tolerant, low-input crop varieties, thereby strengthening India’s agricultural innovation and seed sovereignty.

For decades, farmers have wanted seeds that can grow better with lower inputs – less fertilizer, less pesticides and less water – and still produce higher and more stable yields. Scientists around the world are trying to create such “future ready” crops using various breeding and biotechnology tools. Among these, genome editing has become one of the most powerful and precise ways to improve crops.

How DNA shapes the crops we grow

DNA is the instruction manual within every cell. Over centuries, small natural changes in plants’ DNA, known as mutations, led to useful traits such as larger seeds, better flavor, or greater resistance to pests. Early farmers saved seeds from plants with these helpful changes in DNA, which gradually shaped the food crops we rely on today. When they selected certain plants for breeding, they were choosing specific DNA traits to pass on to the next generation.

With increasing knowledge, farmers and breeders began intentionally cross-breeding two different plant varieties, each with useful properties, to accelerate crop improvement. For example, one type of rice may grow well in drought, while another gives higher yields. By crossing them, breeders hope to create a new plant that has both qualities – drought tolerance and high yield. Cross-breeding is like mixing and matching different sets of DNA of two parent plants to get a better version.

In the mid-20th century, scientists began to use mutation breeding – exposing seeds to radiation or chemicals to create random DNA changes – and selecting rare beneficial mutants. Since then, more than 3,000 improved crop varieties have been produced worldwide using this technology.

Next came genetic modification (GM), which allows scientists to insert a specific gene from an organism into a plant to add useful traits such as insect resistance, herbicide tolerance or improved nutrition. For example, Bt cotton – India’s only commercial GM crop – produces a natural pesticide that protects it from harmful insects. GM technology makes it possible to transfer beneficial genes from any organism into a crop to obtain desired traits.

Genome editing is the most advanced addition to a breeder’s toolbox. CRISPR-Cas, a Nobel Prize-winning technology, works like a pair of molecular scissors to cut and modify plant DNA.

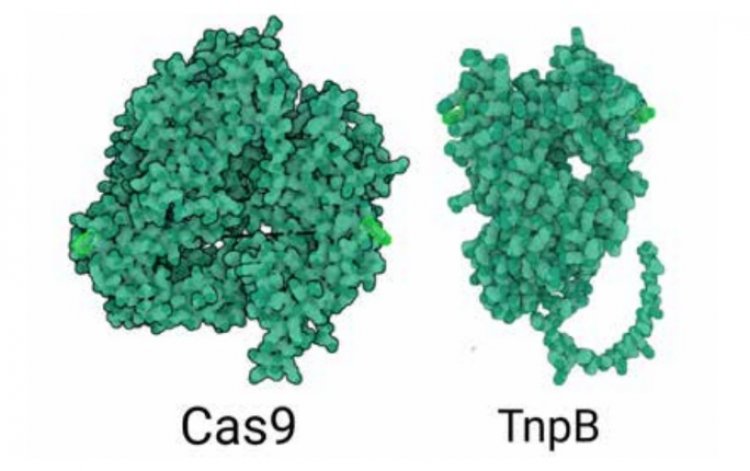

Once the desired change in DNA is made, the CRISPR scissors are no longer needed and can be removed through excision, leaving the plants with only a small, precise edit and no foreign genes. However, CRISPR tools like Cas9 and Cas12a are quite large, making them difficult to deliver to plant cells. Since these devices are patented abroad, Indian scientists often face restrictions in using them for commercial applications. Now, an exciting discovery from India may help overcome this limitation and open new doors to crop improvement.

Researchers at ICAR-Central Rice Research Institute (CRRI), Cuttack, have successfully adapted a small protein called TnpB for targeted genome editing in plants. A patent has recently been granted for this technology, titled “Systems and methods for targeted genome editing in plants.” This is a major achievement for Indian agricultural research and signals the arrival of a new chapter in gene-editing innovation.

What is TNPB and why is it important for Indian farmers?

TnpB is a short alternative to Cas9. To understand TNPB, imagine a pair of scissors. Traditional genome-editing tools like Cas9 are powerful, but they’re like using big garden shears to cut a small thread — they work, yet their large size makes them hard to handle.

In contrast, TNPB is like a small, light pair of scissors. While Cas9 has about 1300 amino acids, TnpB has only 400 – about a third the size. This density makes it very easy to deliver to plant cells, especially through viral vectors or simple transformation methods. Smaller equipment often enables more efficient editing, higher success rates, and lower overall costs.

ICAR granted patent on TnpB

TnpB proteins naturally occur with transposons, which is why they are called transposon-associated protein B (TnpB). But until recently, no one had successfully adapted TnpB as a genome-editing tool for plants.

This is where our group at ICAR-Central Rice Research Institute stepped in. We established a complete TnpB-based genome-editing system that is capable of accurately editing plant DNA. We tested this tool in multiple genes in rice (a monocot) and Arabidopsis (a dicot), and even demonstrated that TnpB can edit more than one gene at the same time. Our findings were published in the internationally renowned Journal of Plant Biotechnology.

Due to the novelty and utility of this work, the Indian Patent Office has granted a full patent for this system. With this intellectual property located in India, Indian researchers will have easy access to this tool to pursue genome editing and crop improvement.

India is becoming a leader in next generation genome editing

Over the years, most genome-editing innovations have come from Europe, the US, and China. The TNPB work of ICAR-CRRI puts Indian science on the global map. This development puts India at the forefront of next generation genome editing.

the way forward

The CRRI team is now working to further refine the tool, expand its use to other crops, and develop a suite of next-generation gene-editing platforms. The discovery could help rapidly develop better crop varieties with increased stress tolerance and lower fertilizer requirements, making farming more economical and flexible.

(Qutubuddin Mollah is Senior Scientist at Crop Improvement Division, ICAR-National Rice Research Institute (NRRI), Cuttack)